ESDEP WG 15A

STRUCTURAL SYSTEMS: OFFSHORE

To describe the general methods of jacket installation. To discuss the various stages of operation from loadout through offshore positioning and installation, including construction practices and equipment. To indicate the calculations normally involved.

Lectures 15A.1: Offshore Structures : General Introduction

Lectures 3.1: General Fabrication of Steel Structures

Lectures 3.2: Erection

Lecture 3.3: Principles of Welding

Lecture 3.4: Welding Processes

Lectures 15A: Structural Systems: Offshore

The phases of installation of a steel jacket - loadout, seafastening, offshore transportation and installation - are described and the associated analyses are indicated.

A steel jacket installation usually consists of the following project phases:

Loadout - Comprises the movement of the completed structure onto the barge which will transport it offshore.

Seafastening - Comprises fitting and welding sufficient structure between the structure and the barge to prevent the jacket shifting during transit to the offshore site.

Offshore Transportation - Comprises the tow to the location offshore and arrival of the barge at the offshore site with the seafastened structure.

Installation - Comprises the series of activities required to place the structure in the final offshore location. These activities include jacket lift and upending, positioning, pile installation, jacket levelling and grouting, together with support services for these activities.

In deciding how best to fabricate (i.e. vertical or on its side) and install (i.e. lifted, launched or self-floating) a given jacket, the options are principally determined by the installation equipment available and the jacket's intended water depth. In general, the preference is to lift the jacket into location. The motivation for this installation method, rather than the more traditional barge-launching, is a reluctance to spend money on jacket steelwork which will only be used during the temporary installation phase. The size of such lifted jackets has been increasing as offshore lifting capacity has grown. With modern lifting capacity now up to 14000 tonnes (see Table 1), jackets approaching this order of magnitude are now candidates for lifting into position.

Figure 1 shows how the 6000 tonne jacket for the Kittiwake field in the North Sea was lifted from the barge into the water and up-ended in a continuous operation, ending with the jacket on the seabed ready for piling. The advantage of this approach is that the jacket, being lowered into the water, does not require the launch frames necessary for launching from a barge. Also, since the weight of the jacket is taken by the cranes throughout, there is no need for special buoyancy tanks and deballasting systems.

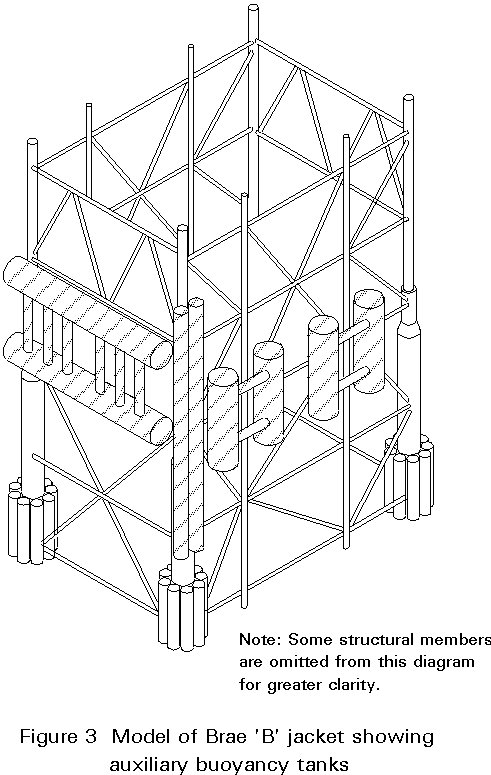

Jackets destined for deeper water are heavier and are usually erected on their side and launched from a barge (Figure 2). This method of construction is currently applicable for jackets up to 25000 tonnes. A launched jacket usually requires additional buoyancy tanks with extensive pipework and valving to enable the legs and tanks to be flooded in order to ballast the jacket into the vertical position on site. For instance, in the case of the Brae 'B' jacket (a large 19000 tonne jacket installed in 100m water depth in the North Sea) it was necessary to provide 11000 tonnes of additional buoyancy. This buoyancy was primarily to limit the jacket trajectory through launch (i.e. to stop it hitting the sea bed) but was also essential for maintaining bottom clearance during up-ending. The additional buoyancy took the form of two 'saddle' tanks, two pairs of twin 'piggy-bank tanks' and twelve 'cigar' tubes installed down the pile guides (Figure 3). Altogether the auxiliary buoyancy added about 3,300 tonnes additional weight to the jacket.

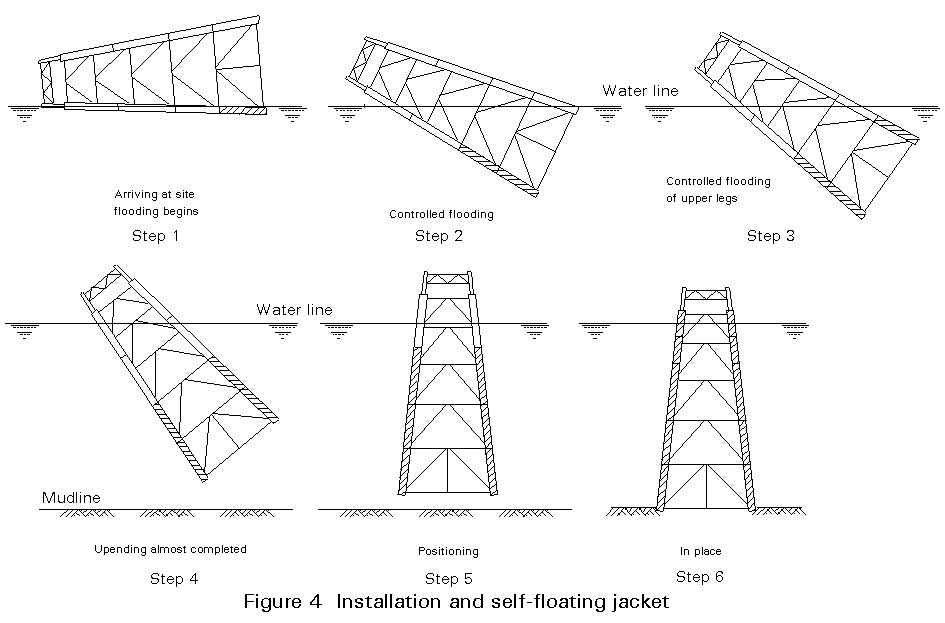

Very large jackets, in excess of launch capacity, have been constructed as self-floaters in a graving dock, towed offshore subsequent to flooding the dock, and installed on location by means of controlled flooding of the legs (see Figure 4).

The installation of a jacket consists of loading out, seafastening and transporting the structure to the installation site, positioning the jacket on the site and achieving a stable structure in accordance with the design drawings and specifications, in anticipation of installation of the platform topsides.

An important aspect is the avoidance of unacceptable risk during offshore activities from loadout through to platform completion. It is recognised that the potential cost to the project associated with failure to successfully execute marine activities is particularly high. Normally therefore the contractor is obliged to produce procedures for these activities which demonstrate that the risk of failure has been reduced to acceptable levels. He is also required to demonstrate that, prior to the commencement of an activity, all the necessary preparations have been completed.

An installation plan must be prepared for each installation. The plan will include the method and procedures developed for the loadout, seafastening and transportation and for the complete installation of the jacket, piles, superstructure and equipment. Depending on the complexity of the installation, detailed procedures and instructions may be needed for special items such as grouting, diving, welding inspections, etc. Limitations on the various operations due to factors such as environmental conditions, barge stability, lifting capacity, etc. must be defined. The installation plan is normally subdivided into phases, e.g., loadout, seafastening, transportation and installation.

Installation drawings, specifications and procedures must be prepared showing all the pertinent information necessary for construction of the total facility on location at sea. These drawings typically include details of all inspection aids such as lifting eyes, launch runners or trusses, jacking brackets, stabbing points, etc. For jackets installed by flotation or launching, drawings showing launching, up-ending and flotation procedures must be prepared. In addition, details are also provided for piping, valving and controls of the flotation system, etc. as well as barge arrangements and tie-down details.

The engineering input into an offshore installation project also involves the design of all temporary bracing, seafastenings, rigging, slings, shackles and installation aids, etc. These must be designed in accordance with an approved offshore design code, e.g. API RP2A [1].

Quality management is a vital and integral component of all offshore installation projects. A general note on Quality Assurance for Offshore Construction is appended to Lecture 15A.8 : Fabrication. It is equally applicable to an offshore installation project.

Loadout entails the movement of the completed structure onto the barge which will transport it offshore. Seafastening entails fitting and welding sufficient ties between the jacket and the barge to prevent the jacket shifting while in transit to the offshore site.

Jackets which have been fabricated on their side are usually loaded by skidding the entire structure onto a cargo or launch barge. During loadout, the jacket is supported on the skid ways, usually on two inner legs of the jacket, see Fig. 9 of Lecture 15A.1. The legs function as the bottom chord of a large truss, which can span between points of support, especially when part of the jacket is on the barge and part still on the skid ways.

Where jackets are fabricated in the vertical, i.e. in the same attitude as the final installation, they may be lifted onto the barge or skidded out. In this latter case, adequate temporary pads and braces must be provided under the columns to distribute the loads during skidding.

Initial friction of the jacket on the skid ways may be as high as 15 per cent, especially if the jacket has been erected with its weight bearing continuously on the skid way. In some cases the jacket is initially fabricated slightly above the skid ways using hydraulic or sand jacks. Then, at the time of loadout, the jacket is lowered onto the skid ways. To reduce the sliding friction, grease on hardwood, or heavy lubricating oil on steel, or even fibre-filled Teflon faced pads, are used. Values of sliding friction as low as 3 per cent are usually attained.

The barge should be of adequate size and structural strength to ensure that the stability and static and dynamic stresses in the barge and seafastenings due to the loading operation and during transportation remain within acceptable limits. The barge must also have the capability to launch the jacket, if this is required, without the use of a derrick barge. For a barge which floats during the loadout, the ballast system must be capable of compensating the changes in tide and loading. It is usual in this case to load out on a rising tide so that the tide assists the ballast system. In the case of a barge which will be grounded during loadout, the barge must have sufficient structural strength to distribute the concentrated deck loads to the supporting foundation material.

The jacket must be loaded in such a manner that the barge is in a balanced and stable condition. Barge stability can be determined in accordance with regulations such as those published by Noble Denton, The American Bureau of Shipping, or the US Coast Guard. Allowable static and dynamic stresses in the barge hull and framing due to loadout, transportation and launching must not be exceeded.

A simplified check list for the operations relating to jacket loadout might be:

Once the jacket is on the barge, the barge must be ballasted for transportation. During loadout, many tanks will be partially full, in order to control deck elevation and trim. However, with the jacket fully supported on the barge, these considerations are no longer relevant and the tanks can be ballasted to suit the demands of the sea voyage. Ballast tanks should normally either be full or completely empty, to eliminate free surface and sloshing effects. The draft and freeboard will have been carefully selected to maximise stability, and especially to minimise submersion of projecting members of the jacket during the tow and the consequent slamming, buoyancy and collapse forces.

Large jacket launch and cargo barges are relatively flexible structures in that the jacket structure is normally (much) stiffer. Therefore, ballasting the barge to obtain the required draft and trim should preferably be done at the dock side before seafastenings are attached. If one scheme of ballasting is to be used for a sheltered channel tow and another for the open sea, the seafastenings should be freed during the reballasting to avoid imposing undue stresses on the jacket legs or, alternatively, calculations should be performed to demonstrate that freeing is not required by the reballasting procedure.

Seafastenings are installed after loadout and must be completed prior to sailaway. They are major structural systems, subjected to both static and dynamic loads. When the barge is on the high seas it must be assumed that it can encounter conditions which are "as bad as could have been statistically foreseen". Accordingly, the gravity and inertial forces involved must be calculated for all anticipated barge accelerations and angles of roll and pitch during the design sea conditions adopted for the tow (usually the 10-year return storm for that season and location). In determining this criteria, the reliability of the short term weather forecast should be considered. Since the loads are dynamic, impact must be minimised. Seafastenings should be attached to the jacket only at locations approved by the designer. They should be attached to the barge at locations which are capable of distributing the load to the barge internal framing. They should also be designed to facilitate easy removal on location. Seafastenings are normally subject to the same code requirements for fabrication as the jacket.

The transportation of heavy components from a fabrication yard to the offshore site is a critical activity. It is especially so in the case of the jacket since the behaviour of the unit usually influences the verification of barge strength, the design of seafastenings, and indeed the design of the jacket itself. Also there are the practical aspects of tug selection, tow route, etc. to be considered.

The size and power requirements of the towing vessels and the design of the towing arrangement must be calculated or determined from past experience. Tug selection involves such considerations as length of tow route, proximity of safe harbours and the anticipated weather conditions and sea states. As a minimum the tugs should be capable of maintaining station in a 15 metre/second wind with accompanying waves. However, this criterion depends on the location. For instance, the requirement in the Mediterranean is typically that the main tug should maintain station against a 20 metre/second wind, 5,0m significant sea-state and 0,5 metre/second current, acting simultaneously. Weather forecasting is provided throughout the tow so that, if exceptional weather threatens, a pre-arranged port of refuge may be sought.

Experience has shown that the first phase of transportation is the most treacherous. There are several reasons for this. In the harbour area a big tug can normally exercise very little control even with a shortened towline. With a short towline between two considerable masses, the large tug and the much larger barge/jacket, the risk of snapping is high. Thus it is standard practice to lengthen the towline once out of the port. Also, because of the nature of many ports, close control is essential in order to avoid the possibility of running aground. Normally, therefore, the harbour tugs take the barge out under the guidance of a pilot who knows the port. When the barge is out of the port the problems are not totally solved since it must be assumed that the worst can happen, i.e. the towline may break.

The tug must have sufficient time to pick up the emergency towline and control the barge before it drifts into shallow water. Thus the departure is normally subject to strict weather forecast conditions for a period which assumes that the speed of the tow is between 1 and 2 knots for the first 100 nautical miles from the coast. Consequently, as a minimum, a favourable 48-hour weather forecast is required, e.g. Force 5 and decreasing.

Once the tow is under way, trim will be adjusted to optimise tow speed and give directional stability during tow. Usually the barge will be trimmed down by the stern.

The behaviour of the jacket seafastened to the barge must be satisfactory both from the point of view of static and dynamic stability. Both are verified by means of numerical analyses. However, particularly for larger structures, the sensitivity of the dynamic analysis will usually warrant verification by model testing.

The intact static stability criteria usually adopted is that the righting arm be positive throughout a range of 36° about any axis. The so-called dynamic stability of wind overturning criteria simply ensure that for a given wind, the energy which tends to overturn the barge is at least 40% less than that which is available due to the inherent righting stability of the barge.

In considering the motions of the jacket and barge it is intuitively plausible that roll will be the most problematical motion (from the point of view of body accelerations) and that the largest roll will be caused by a beam sea. It may be less obvious, but nevertheless true, that if the barge width and, to a lesser extent the length, are reduced, the roll will diminish and if the barge is set at a (much) deeper draft, the roll will also diminish. All of these considerations reflect static properties of the jacket and barge. Improvements can occasionally be made by choosing a narrower barge (although obviously stability will suffer) or increasing the draft (although in this case stability may again suffer and parts of the structure which were previously 'dry' may now be subjected to 'slamming'). Incorrect "balancing" of these aspects can have very serious cost/risk implications in overall project terms. Thus, for a large jacket, the barge selection process is normally performed at a very early stage of the design process.

This section is concerned with the stages of jacket installation commencing with removal of the jacket from the barge to its placing on the sea bed and temporary on-bottom stability. Lecture 15A.6: Foundations covers the subject of pile installation.

Unless a jacket is a self floater, it must first be removed from the transportation barge. There are two basic methods used:

The launch site is normally at or near the installation location. With heavy jackets in shallow water it may be necessary to launch the jacket in deep water at some distance from the installation location and tow the jacket to site.

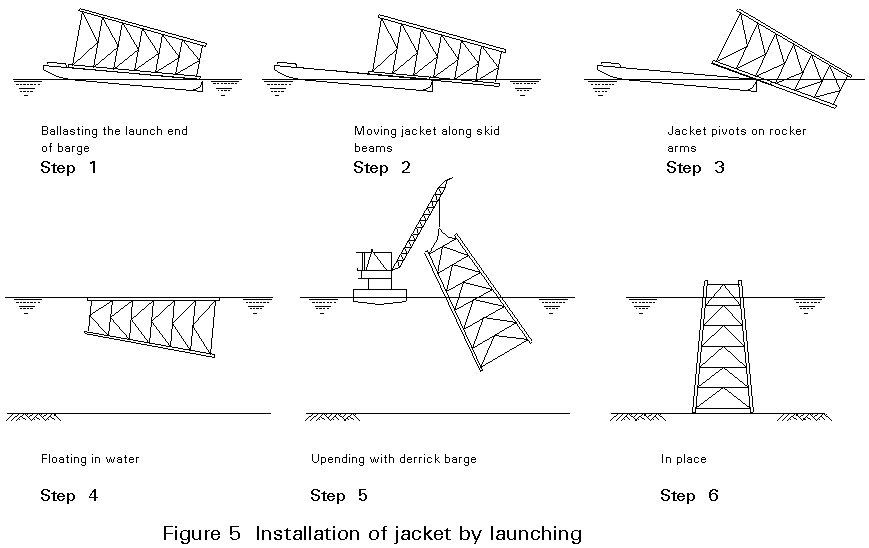

Immediately prior to launch, the seafastening securing the jacket to the barge is cut. The jacket is then pulled along the barge skid ways (which were used for loadout) by winches. As the jacket moves towards the stern of the barge, the barge start to tilt and a point is reached when the jacket is self sliding. An initial tilt to the barge may have been provided by ballasting immediately prior to launch. A stern trim of approximately 5° is usually aimed for.

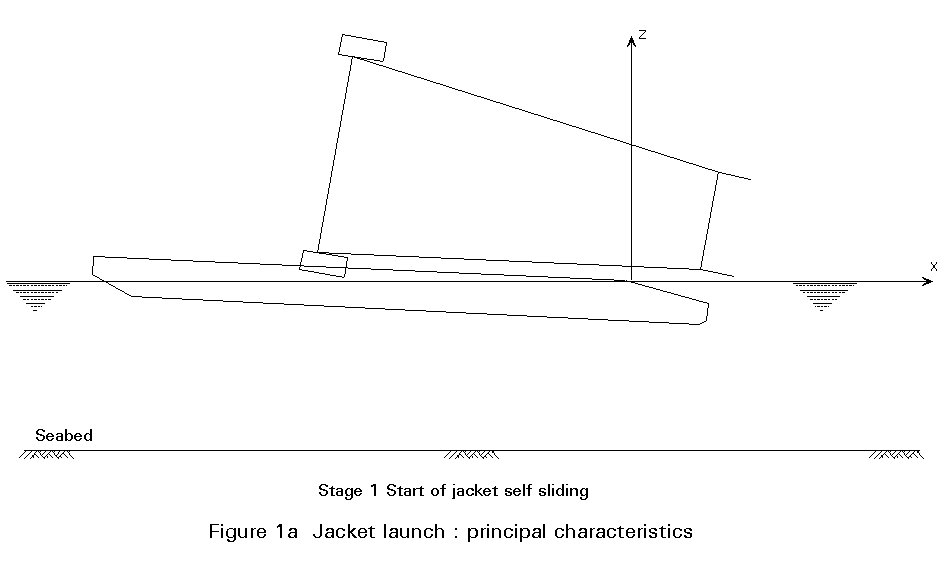

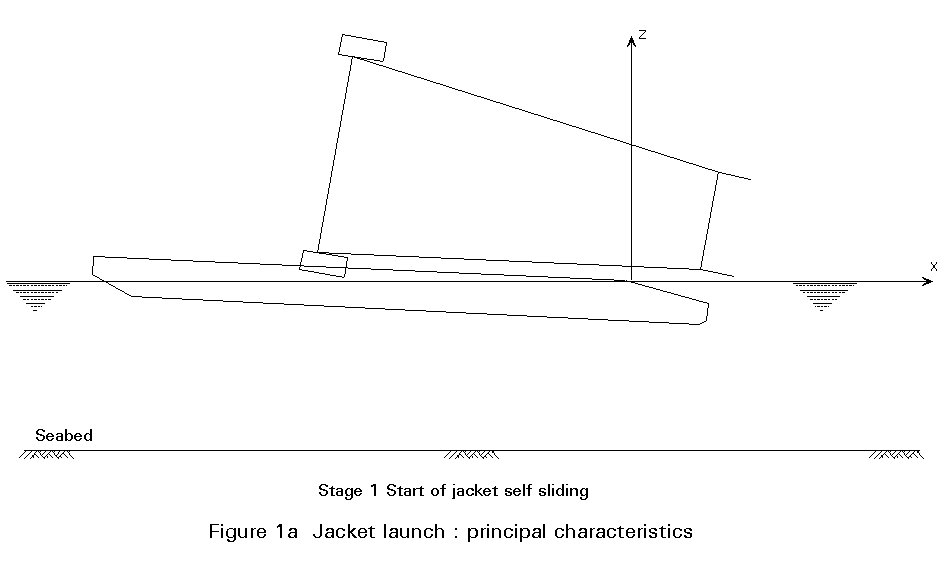

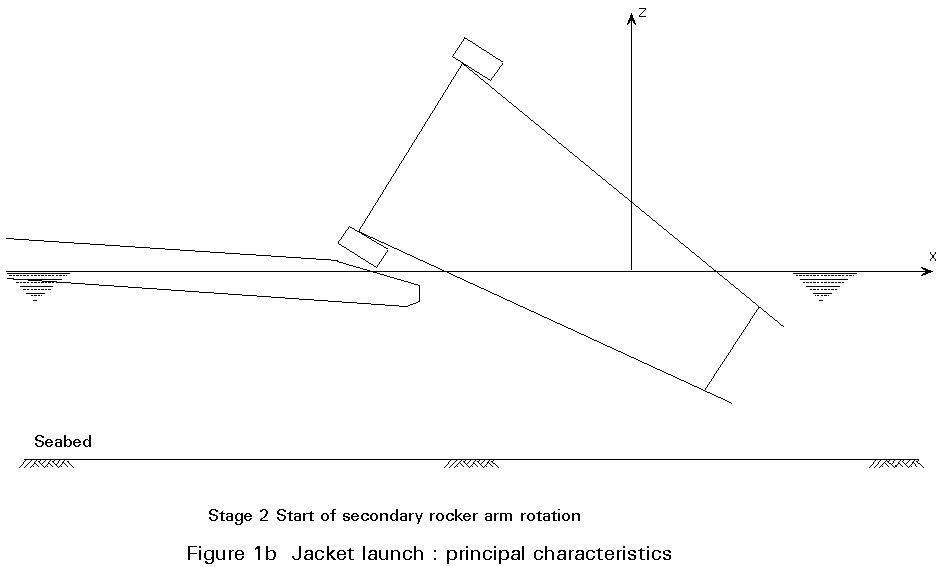

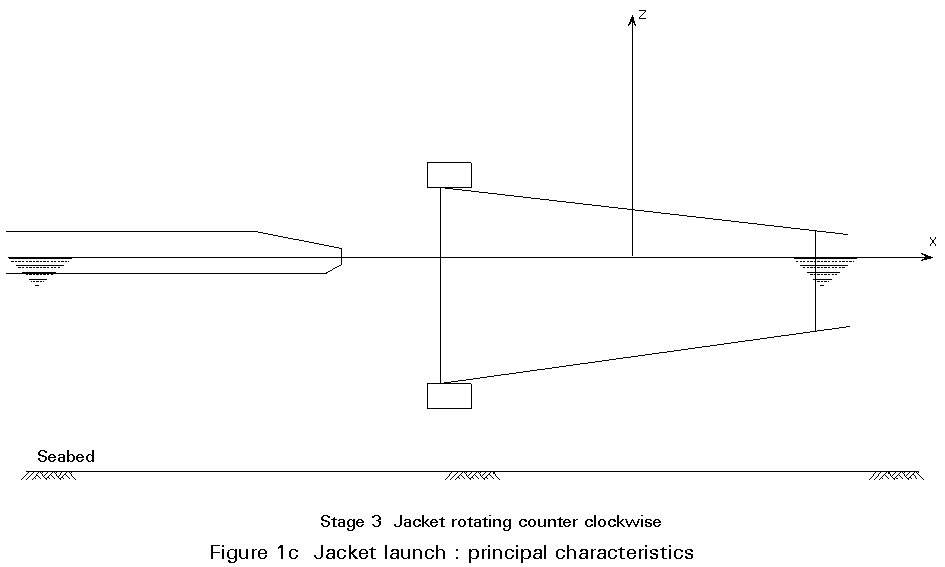

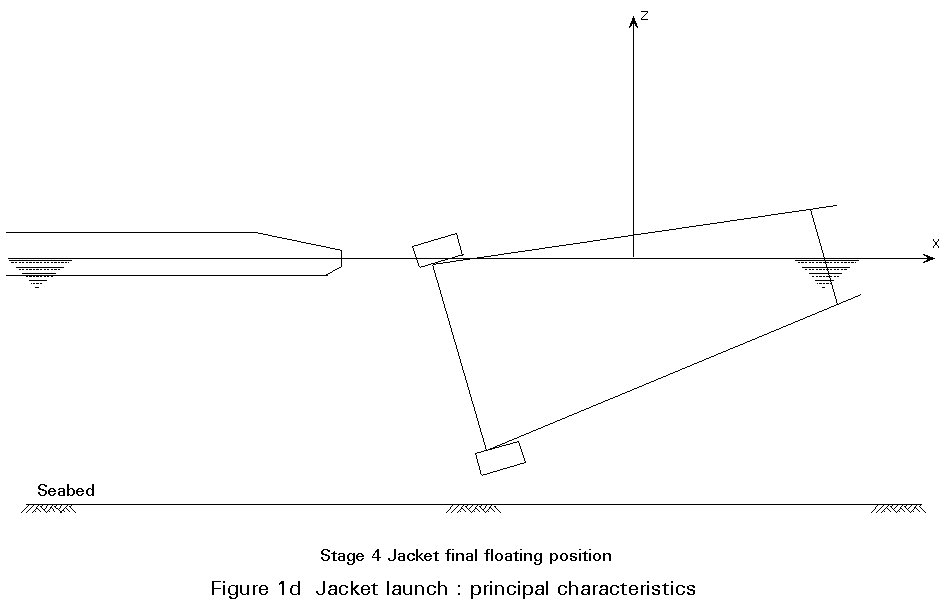

The skid ways terminate in rocker arms at the stern of the barge. As the jacket moves along the skid ways its centre of gravity reaches a point where it is vertically above the rocker arm pivot. Further movement causes the rocker arm and jacket to rotate. The jacket will then slide under its own self weight into the water. Various stages in the launch of a jacket are shown in Figure 1a to 1d.

Once in the water the self floating jacket is brought under control with lines from tugs and/or the installation vessel.

The jacket must be designed and fabricated to withstand the stresses caused by the launch. This can be achieved either by strengthening those members which might be over-stressed by the launching operation, or designing into the jacket a special truss, commonly referred to as a launch truss. Spacing between jacket members or launch trusses will be dictated by the spacing between launch skid ways. Thus a jacket will generally be designed from the outset for installation by a specific barge.

Once launched the jacket must float with a reserve of buoyancy in order to stop the downward momentum of the jacket. This requires the jacket to be water tight. It is common practice to gain additional buoyancy by sealing jacket legs and pile sleeves with removable rubber diaphragms. However, there is frequently a need for even more buoyancy. This is achieved by adding buoyancy tanks. These need to be removable and are located where they give most benefit. Buoyancy tanks from previous launches are often used.

The launch of a jacket is clearly a critical phase in the life of the jacket. Considerable design effort is required in order to ensure that the launch sequence is feasible. A jacket launch naval analysis is required in order to:

The plots shown in Figures 1a to 1d are extracted from such an analysis. The jacket weight was 14,000 tonnes and was being installed in 105 metres of water. The analysis showed that it should take approximately 2 minutes between start of self sliding (Figure 1a) and the jacket reaching its final floating position (Figure 1d).

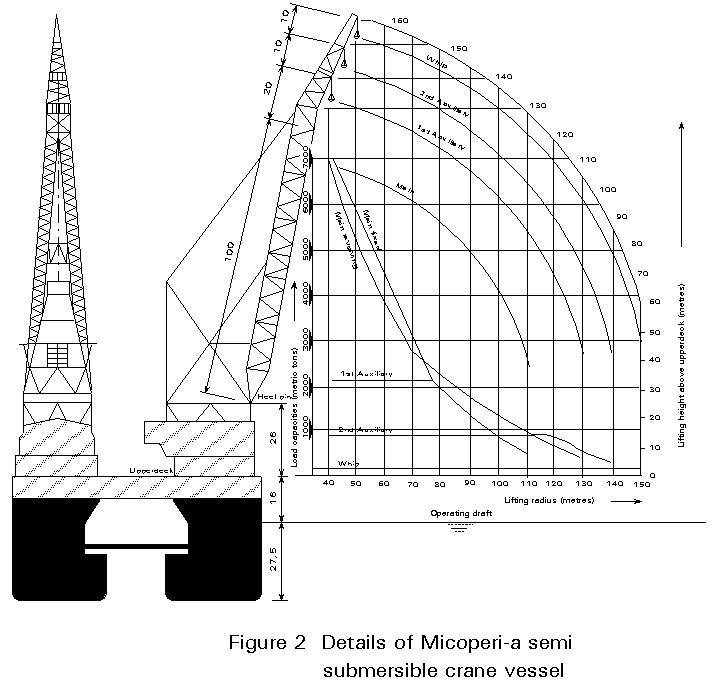

An increasing number of jackets are being installed by direct lift. This trend has been encouraged by the availability of large crane vessels such as the Micoperi 7000. Curves showing load capacity against lifting radius are shown in Figure 2. Another factor tending to increase direct lift jackets are savings in weight that are being achieved in jacket design.

In a direct lift the jacket is lifted off the barge completely in air. A second form of lift is the buoyancy assisted lift. In this case the barge is flooded and hence submerged. This results in part of the jacket being buoyant, reducing hook loads. Buoyancy tanks may be added to the jacket if required.

Shallow water jackets may be lifted in the vertical position. In this case no up-ending is required and installation is straight forward. Deep water jackets will in general be lifted on their side. Two cranes will normally be used, noting that large derrick barges such as the Micoperi 7000 are fitted with two cranes as standard. When considering a tandem lift it should be noted that it is unlikely that both hooks will carry the same load, and that the maximum permissible jacket weight will be less than the sum of the two crane capacities. It should also be noted that cranes are frequently guyed back to give maximum lift capacity and carry less load if they are revolving. This can further reduce the apparent lift capacity. Finally, the weight of lifting slings need to be considered, these contributing as much as 7% of the lift weight.

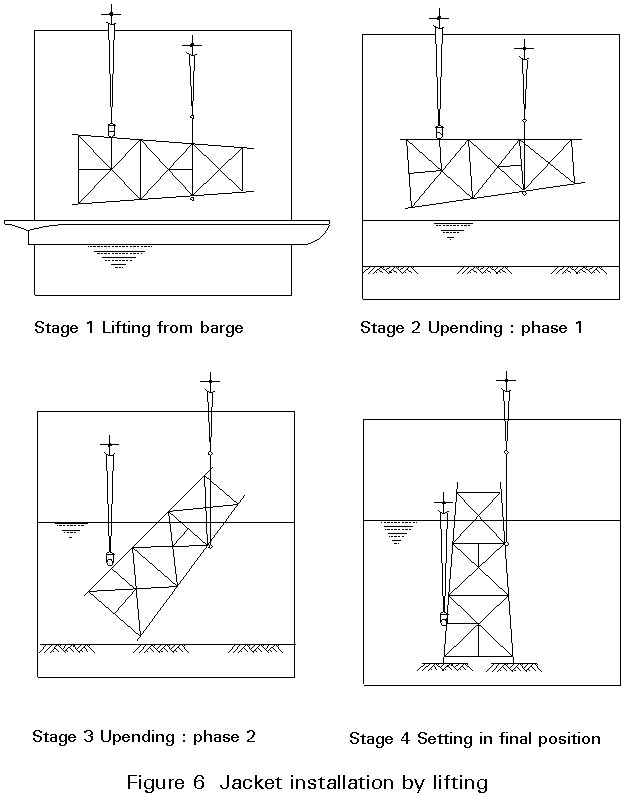

When the jacket is to be removed from the transportation barge by lifting, it is normal for the installation vessel to be correctly moored and positioned so that up-ending and set-down may proceed as one integral lift operation.

The selection of a suitable installation vessel is clearly essential. In addition to lift capacity, it is also necessary to consider stability and motion response characteristics. In the harsh North Sea environments installation vessels are usually semi-submersibles such as the Micoperi 7000. In more moderate waters they are often flat bottomed barges. In intermediate environments, e.g., the Gulf of Mexico, ship-shaped vessels may be used.

The large semi-submersible crane vessels used in the North Sea have full dynamic positioning systems for locating themselves on site. They also have sophisticated computer controlled ballast systems to keep the vessel level during lifting operations. During a lift the ballast system is also used to counteract heel and increase hoisting and lowering speeds during the crucial lift-off and set-down operations.

The natural period of large installation vessels in roll, pitch and heave tend to be close to the typical peak periods of the sea spectra encountered offshore. These motions therefore predominate. Normally this means that beam seas should be avoided since this excites roll which is the most disruptive motion. However, the "best attitude" is not always possible since it depends on the work that the vessel is required to perform. Accordingly vessel operators perform extensive studies to determine permissible sea states for specific operations and vessel captains invariably "experiment" with different headings in a particular sea in order to minimise motions and maximise workability.

The first stages in lifting a jacket from the transportation barge involve positioning the barge and connecting the slings to the hook. The barge will normally be controlled by tugs. Once everything is ready for lift to proceed the seafastenings will be cut. The next stage is to transfer the weight of the jacket from the barge to the crane. The general requirement here is to lift as rapidly as possible. However, careful control and phasing with barge and crane vessel motions is required in order to ensure that once the jacket is lifted clear of the barge it does not hit the barge as a subsequent wave passes through. The same lift procedure is adopted in both a direct and buoyancy assisted lift.

Once the jacket is lifted clear of the barge, the barge is removed by tugs. Up-ending of the jacket will then normally proceed directly.

Unless a jacket is transported and lifted in its upright position, it will be necessary to up-end the jacket at the installation location. Up-ending may be achieved by controlled flooding of buoyancy tanks, by using a crane vessel or by a combination of both.

A large crane vessel will not normally be required for either a launched or self-floating jacket. Upending is therefore achieved by controlled flooding. A small installation vessel will usually be required for the installation of piles once the jacket has been set-down, so this is used as the platform from which to control the various flooding operations. This installation vessel will also be used to help position the jacket.

Figure 3 shows a sketch of the Brae 'B' jacket showing the auxiliary buoyancy tanks. In this case the flooding system involved 42 primary and 22 contingency subsea valves under direct hydraulic control. The nitrogen power source and associated control panels were contained in watertight capsules.

Figure 4 shows a sequence of sketches indicating how a self floating jacket is upended. In step 1 the waterline compartments at one end of the jacket are flooded. More water line tanks are flooded in step 2 until by step 3 the upper frame of the jacket reaches waterline and may also be flooded. The jacket is then allowed to rotate until all legs are equally flooded as in step 4. The jackets natural position will then be floating upright as in step 5. Further flooding of the jacket as in step 6 will enable the jacket to be lowered onto the sea bed in a controlled manner.

The up-ending of a launched jacket will be similar to that shown in Figure 4. The main difference is that there may be less excess buoyancy with which to control the operation. In this case a combination of flooding and lift, as shown in Figure 5, may be used to up-end and set-down the jacket.

The crane and ballasting operations need to be clearly defined before the operation begins. This involves careful naval analysis of the free floating position of the jacket at various stages during the up-ending procedure. A feature of these analyses is the need to consider what happens in the event of buoyancy tanks being accidentally flooded, or of flooding valves failing to operate. Contingency procedures and equipment must be provided.

Figure 5 shows the most simple use of a crane to up-end and set-down a jacket. This is acceptable for jackets that are launched. For horizontally oriented jackets that are lifted directly the procedure is more involved.

A horizontally lifted jacket may be upended in one of two ways. Perhaps the most straight forward is to lower the jacket into the water so that it floats. Slings can then be removed and new slings attached at the top of the jacket. The jacket may then be up-ended as shown in Figure 5. This may require closures to legs and some additional buoyancy.

A second method is to up-end directly, as shown in Figure 6. This requires special padears so that the necessary rotation between slings and jacket can occur. Careful naval analysis is also required in order to carefully determine hook loads and to ensure that the jacket remains stable.

Once up-ended the jacket can be set-down on the sea-bed. Since the lifting points are submerged divers may be required to disconnect the slings from the jacket.

Although two crane hooks are shown in Figure 6, it should be noted that for light weight jackets it is possible to up-end using a single crane. In this case the main and auxiliary hooks are used together, for example the main hook taking the weight of the jacket with the auxiliary hook providing the upending force.

An increasing trend is to install a jacket over an existing well or wells. A pre-drilling template will have been used to position the wells, the same template being used to position the jacket. It is necessary to ensure that the well heads are protected from damage due to accidental contact with the jacket.

Once set-down the jacket should be positioned at or near grade and levelled within the tolerances specified in the installation plan. Once level, care should be exercised to maintain grade and levelness of the jacket during subsequent operations. Levelling the jacket after all piles have been installed should be avoided if at all possible as it is costly and frequently ineffective. If necessary, levelling should take place after a minimum number of piles have been driven by jacking or lifting. In this instance procedures should be used to minimise bending stresses in the piles.

Once set-down on the sea bed, it is normal for piling to proceed as rapidly as possible. However, this far into the installation procedure the weather and hence sea conditions may be detioriating. This is a result of long term weather forecasting being less reliable than short term forecasting. It should also be noted that any problems encountered during the installation procedure will result in delay and that it may be some time before the jacket is adequately fixed to the sea bed by piling.

It is necessary for the jacket to be stable and level during piling. A separate on-bottom stability analysis is therefore carried out. Three conditions need to be met:

(1) vertical resistance to jacket weight and piling loads;

(2) stability against sliding under wave/current loading;

(3) stability against overturning under wave/current loading.

In carrying out the above analyses it is necessary to use an appropriate sea-state to generate hydro-dynamic loading. This should be the maximum statistical wave which may occur prior to piling being completed. Assuming installation to occur in the summer months, a typical criteria may be a 1 year summer storm wave.

The provisions that need to be made to ensure on-bottom stability vary greatly depending on jacket location, height and on sea-bed soil conditions. For example, with good soil conditions the jacket may be able to be supported directly on existing jacket steel with no extra provision made. However, with poor soil conditions large 'mudmats' may be required in order to spread the load. These can influence launch and installation dynamics.

For many jackets it is not possible to achieve stability against sliding and overturning using flat mudmats. In these circumstances mudmats with skirts may be used. Skirts considerably improve the resistance to sliding, and in silty or clay soils can allow nominal tension loading to resist overturning. Another option frequently used is to stab a number of piles as soon as the jacket is set-down. These will penetrate some distance under self weight providing additional sliding resistance. Since most piles are inclined, the piles also provide a degree of resistance to over turning.

[1] API RP2A, Recommended Practice for Planning, Designing and Construction of Fixed Offshore Installations, latest edition. Engineering design principles and practices that have evolved during the development of offshore oil resources.

|

Operator |

Name |

Type |

Mode |

Lifting Capacity |

|

Heerema |

Thor |

Monohull |

Fix Rev |

2720 1820 |

|

Odin |

Monohull |

Fix Rev |

2720 2450 |

|

|

Hermod |

Semisub |

Fix Rev |

4536 + 3628 = 8164 3630 + 2720 = 6350 |

|

|

Balder |

Semisub |

Fix Rev |

3630 + 2720 = 6350 3000 + 2000 = 5000 |

|

|

McDermott |

DB50 |

Monohull |

Fix Rev |

4000 3800 |

|

DB100 |

Semisub |

Fix Rev |

1820 1450 |

|

|

DB101 |

Semisub |

Fix Rev |

3360 2450 |

|

|

DB102 |

Semisub |

Rev |

6000 + 6000 = 12000 |

|

|

Micoperi |

M7000 |

Semisub |

Rev |

7000 + 7000 = 14000 |

Notes:

Table 1 Major Offshore Crane Vessels